Introduction

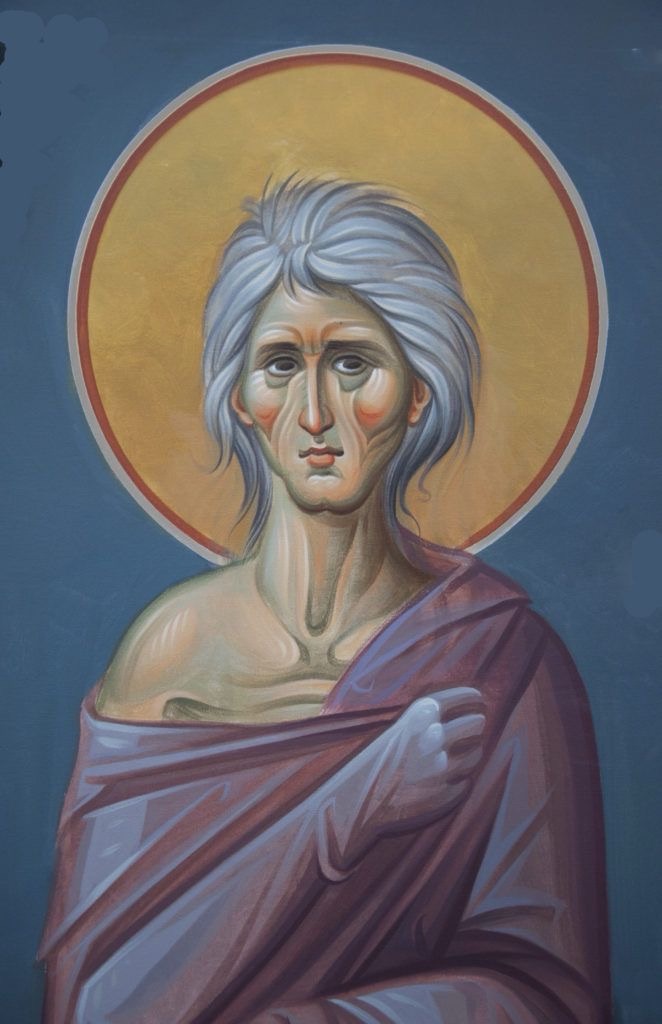

Mary of Egypt’s story is a compelling narrative of transformation: a woman who, after living a life of sexual promiscuity in Alexandria, undergoes a profound shift and retreats to the desert to pursue a life of solitude and repentance. For decades, she dedicates herself to prayer and penance, ultimately achieving a state of holiness recognized by the monk Zosimas, who encounters her near the end of her life. Traditionally, her tale is set against a backdrop of societal moral decline, with her strive for purity serving as a beacon of redemption and hope. When viewed through an existentialist lens—a philosophy emphasizing individual freedom, choice, and the creation of meaning in an indifferent universe—Mary’s journey transcends its religious roots. It becomes a powerful testament to personal agency, authenticity, and self-definition in a world lacking inherent moral absolutes.

Existentialism and the Quest for Authenticity

Existentialism, as articulated by thinkers like Jean-Paul Sartre, posits that “existence precedes essence.” Individuals are not born with a fixed purpose; instead, they define themselves through their actions and choices. Mary of Egypt’s life embodies this principle. Initially, she exists as a prostitute, her identity shaped by societal circumstances and personal decisions. Yet, her radical choice to abandon this life and embrace asceticism marks a pivotal act of self-redefinition. She rejects the essence imposed upon her and forges a new identity through her own volition.

From an existentialist perspective, Mary’s strive for purity is not merely a religious pursuit of virtue but a quest for authenticity. Authenticity, in this context, means living in alignment with one’s freely chosen values rather than those dictated by external forces. Her retreat to the desert symbolizes a confrontation with the existential condition: the need to create meaning in a universe that offers no inherent purpose. In the solitude of the desert, free from societal expectations, Mary faces her freedom and the responsibility it entails. Each day she chooses to stay, to pray, and to repent reaffirms her commitment to the essence she has crafted for herself.

Divine Intervention and Personal Responsibility

Mary’s transformation is often attributed to divine intervention. According to tradition, she is barred from entering a church in Jerusalem by an invisible force, which she interprets as a sign from God or the Virgin Mary, sparking her repentance. This might suggest a loss of agency, conflicting with existentialism’s emphasis on human freedom. However, existentialist thought, particularly Søren Kierkegaard’s, accommodates faith as a personal choice. Kierkegaard’s “leap of faith” is an individual act of will, embracing belief amid uncertainty. Similarly, Mary’s response to this divine sign can be seen as her decision to reinterpret her life’s direction. The initial spark may come from an external event, but it is her sustained choice to live a life of penance that defines her.

Existentialism stresses personal responsibility, regardless of external influences. Mary’s decades in the desert are not a passive endurance but an active, repeated affirmation of her will. Her strive for purity thus becomes an assertion of agency, aligning her actions with her self-determined values rather than a mere submission to divine command.

Confronting Angst and the Absurd

Existentialism explores angst—the anxiety stemming from recognizing one’s freedom—and the absurd, the lack of inherent meaning in the universe. Mary’s crisis at the church door can be seen as such a moment. Barred from entry, she confronts her past choices and the potential meaninglessness of her existence. This despair becomes the catalyst for her to take responsibility and create her own purpose.

The desert amplifies this existential encounter. A barren, indifferent landscape, it mirrors the absurd: a world unconcerned with human morality or aspirations. Yet, within this void, Mary asserts her freedom. By choosing a life of prayer and repentance, she imposes meaning onto an otherwise indifferent existence. Her strive for purity is not an escape but a bold engagement with the absurd, refusing nihilism and forging a path of personal significance.

Purity as Self-Definition

Set in a time of falling morals, Mary’s story is often framed as a moral exemplar, urging a return to Christian virtues. Existentialism, however, views morality as a personal construct rather than a universal standard. Mary’s purity is not just adherence to religious ideals but a self-defined ethic. By withdrawing from society, she rejects its moral decay not through conformity but through radical nonconformity. She does not aim to reform the world; she transcends it, crafting a personal code that contrasts sharply with her surroundings.

This reframes her strive for purity as an existential endeavor. It is less about achieving sinlessness and more about aligning her actions with her chosen identity. In a society where morals falter, Mary’s purity emerges as a testament to authenticity—a life lived true to her own values, independent of external validation.

The Role of the Other and the Final Act

Mary’s encounter with Zosimas introduces the existentialist concept of the Other, through whom we partially define ourselves. Zosimas recognizes her holiness, and through his gaze, she sees herself as redeemed. Yet, Mary does not depend on this recognition. Having lived decades in solitude, she is secure in her self-definition. Her request for communion is a final affirmation of her journey, not a plea for approval.

By sharing her story with Zosimas, Mary completes her existential project. She articulates her narrative, ensuring her self-created meaning endures. This act, chosen on her terms, underscores her freedom, culminating her life’s work as she prepares for death.

Conclusion

From an existentialist perspective, Mary of Egypt’s strive for purity transcends traditional narratives of sin and redemption. It is a story of radical freedom, personal responsibility, and the creation of meaning in an indifferent universe. In a time of falling morals, she neither conforms to societal norms nor seeks to repair them. Instead, she withdraws to the desert, confronting the void and defining her essence through her choices. Her purity is not a return to conventional virtues but an assertion of authenticity—a life aligned with her self-determined values. Mary’s journey resonates as a timeless reflection of the human struggle to find purpose and integrity amid existential uncertainty.

Daniel B Guimaraes, MD MSc

Leave a comment